In a recent essay for Social Science & Medicine–Mental Health, epidemiologist Catherine Gimbrone and coauthors identified a significant gap in depressive attitudes between liberal and conservative teens. This gap was present in all years observed in the study (2005–18). It grew significantly starting in 2012, however, as depressive affect unilaterally spiked among liberals. Three years later, conservatives also began reporting increases in depression—although that rise tapered off relatively quickly while the increases among liberals continued.

Liberal girls tended to be significantly more depressed than boys, particularly after 2011. However, ideological differences swamped gender differences. Indeed, liberal boys were significantly more likely to report depression than conservatives of either gender. The authors also found that the more educated a teen’s family was, the more likely the young people were to be depressed, and the more dramatic their rise in depression was after 2012.

Why is it that liberal teens are more consistently depressed than conservatives? Why might familial education correlate with heightened depression for liberal youth? Why was there a spike in depression (and a growing ideological divergence in depressive affect) after 2011, corresponding with the onset of the “Great Awokening”? This essay will provide a deep dive into the literature on the relationship between ideology and subjective well-being in the hopes of shedding light on possible answers to these questions.

Conservatives Are Happier than Liberals

Although the study by Gimbrone et al. was focused on trends among young people, the well-being gap between conservatives and liberals is not unique to youth. The gap manifests clearly across all age groups and is present as far back as the polling goes. In the General Social Survey, for instance, there has been a consistent 10 percentage point gap between the share of conservatives versus liberals who report being “very happy” in virtually every iteration since 1972 (when the GSS was launched).

Academic research consistently finds the same pattern. Conservatives do not just report higher levels of happiness, they also report higher levels of meaning in their lives. The effects of conservatism seem to be enhanced when conservatives are surrounded by others like themselves. However, in an analysis looking at ninety countries from 1981 through 2014, the social psychologists Olga Stavrova and Maike Luhmann found “the positive association between conservative ideology and happiness only rarely reversed. Liberals were happier than conservatives in only 5 out of 92 countries and never in the United States.”

It is empirically unclear why this pattern is so ubiquitous, not just in the contemporary United States but also historically (virtually as far back as the record goes) and in most other geographical contexts as well. There are a handful of prominent theories.

Conservatives are more likely to be patriotic and religious. They are more likely to be (happily) married and less likely to divorce. Religiosity, in turn, correlates with greater subjective and objective well-being (here, here, here). So does patriotism. So does marriage. Consequently, some have argued that the apparent psychological benefit of conservatism actually comes from feeling deeper connections with one’s country, one’s family, and the Divine. On this model, conservatism itself would be largely incidental to the happiness gap. A liberal who was similarly religious, or patriotic, or had a similarly happy marriage, would be expected to have similar levels of happiness as conservative peers.

In a similar vein, studies have repeatedly found that conservatives—both politicians and laymen—tend to be more conventionally attractive than liberals (and have better sex lives). Moreover, people who are healthier in childhood have been shown to be more likely to become conservative as adults. Meanwhile, people with high measured cognitive ability are also more likely to support economic conservatism (and cultural liberalism).

In response to findings like these, some have speculated that the natural advantages and better treatment that some people enjoy predispose them toward conservatism (to justify the inequalities they benefit from). The happiness gap between liberals and conservatives may, in turn, be a simple product of the reality that conservatives tend to find themselves in more fortunate social positions (more attractive, healthy, intelligent, socially integrated). And conservatism may help these folks maintain their happiness by legitimizing the privileges they exploit to maintain or enhance their social position.

There are, however, some deep problems with these hypotheses. For one, the relationship between certain advantages and conservatism likely flows both ways. For instance, conservative belief in personal responsibility and agency may help explain observed differences in physical health and appearance (due to conservatives trying to control what they can control in their lives through diet and exercise) rather than positive physical attributes driving people towards conservatism.

Conservatism may likewise render people more likely to get married and stay married. Hence even if it were established that differential patterns of marriage rather than conservatism per se drives the happiness gap, insofar as conservatism is a critical influence on differential marriage outcomes, ideology would still significantly influence happiness in an indirect way.

Likewise, political scientist Ryan Burge has demonstrated that independent of religious attendance, liberals are roughly twice as likely to report mental illness as conservatives. This is just as true for people who regularly attend religious services as it is for people who never attend.

Religiosity does provide benefits independent of conservatism. Nevertheless, Burge demonstrates, the effects of religion are dramatically enhanced among conservatives in a way that is distinct from moderates and liberals. The well-being gap is not simply a product of conservatives being more religious, it also seems to be a product of conservatism itself, and it manifests even when controlling for level of religiosity.

Yet the most challenging fact pattern for the “privilege plus system justification” narrative of the ideological happiness gap is that, as I spell out in my forthcoming book (and this talk), wealth increasingly correlates with liberal political parties and views in the United States and many other countries. That is, the “winners” in the current economy are increasingly the people who are most depressed. This is hard to explain if the happiness gap is purely a function of privilege.

Furthermore, immigrants and minorities in the United States are more likely to be religious and socially conservative as compared to native-born whites. Likely not coincidentally, immigrants and racial or ethnic minorities are also significantly less likely to be diagnosed with depression as compared to non-Hispanic white peers. This is likely not a result of the “privilege” they enjoy relative to native-born non-Hispanic whites.

In a similar vein, conservatism has been shown to have even larger well-being effects for senior citizens than younger people. It helps adherents preserve a sense of value, meaning, and self-esteem even when they are no longer as physically vital, sexually attractive, mentally acute, or economically productive as they once were.

Likewise, the relationship between conservatism and happiness is especially pronounced in countries facing threat or adversity (and the well-being benefits of religion and patriotism are also enhanced by adverse material circumstances)—further undermining the idea that the relationship between conservatism and happiness is driven primarily by social advantage and system justification.

Instead, it seems likely that conservatism and ideological fellow travelers (religiosity, patriotism) may help people make sense of, remain resilient in the face of, and respond constructively to inequality and misfortune, irrespective of where they fall on the social strata. Liberal ideology, by contrast, may not provide the same benefits to adherents.

Liberals Are Far More Likely to be Depressed, Anxious, or Otherwise Neurotic Compared to Conservatives

Conservatives report significantly higher levels of happiness than liberals. On the other end of the spectrum, liberals are significantly more likely to experience adverse mental and emotional conditions. Some have argued that these differences in negative psychic states may explain most of the persistent divergence between liberals and conservatives in subjective well-being measures.

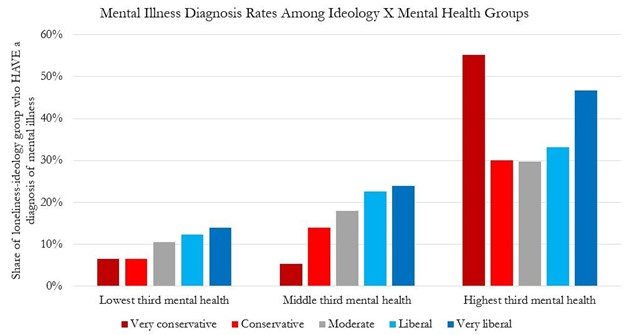

In any case, investigations consistently find that people who identify with liberal ideology are significantly more likely than others to be depressed, anxious, and to rank high on neuroticism (here, here). Liberals are also much more likely than conservatives to be diagnosed with mental illnesses or disorders. As Jonathan Haidt recently illustrated with Pew Research data, these trends hold across genders and across age groups.

Contemporary young people are more likely to be diagnosed with a mental condition than older Americans. Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a psychiatric condition than men—and the gaps are much larger among contemporary cohorts as compared to earlier ones (incidentally, the political and ideological gap between men and women has grown over this same period). However, across all age groups and for both genders, liberals are roughly twice as likely as conservatives to report being diagnosed with a mental illness.

What’s going on here?

Explaining these patterns is actually somewhat difficult, in part because social researchers lean liberal over conservative at a ratio of more than ten to one. As a consequence, scholars tend to spend a lot of their energy defining conservatism and Republican voting behavior in terms of deficits and pathologies, or otherwise blaming the political Right for unfortunate states of affairs.

As we have seen, even the conservative advantage in happiness has been broadly defined as pathological in the literature—portrayed as an outgrowth of privilege, system justification, and a lack of awareness or empathy. In a scholarly environment where well-being is defined in pathological terms when experienced by conservatives, one should not be surprised that there is comparably little work exploring how and to what extent liberal ideology may contribute to unfortunate patterns of cognition or behavior, or adverse states of affairs. Yet there are some plausible hypotheses that have compelling empirical support.

Explaining the General Link between Liberalism and Mental Illness or Disorders

It’s possible that genetics and biology could explain much of the observed relationship between liberal identification and mental illness. After all, there is robust evidence that individuals’ political, ideological, and moral dispositions are biology-based and heritable to a significant degree (here, here, here, here, here, here). One might hope that cultural interventions such as education could help people transcend biological differences and approach common ground. However, the opposite seems true: cognitive sophistication reinforces and exacerbates intrinsic differences rather than reducing them.

Incidentally, psychological dispositions and disorders are also significantly influenced by genes and biology. They, too, are quite heritable (here, here, here, here, here, here). Cognitive sophistication likewise tends to exacerbate ideological differences rather than ameliorating them.

Consequently, it could be that the observed correlation between liberalism and mental illness is a product of some common set of biological or genetic factors that simultaneously predispose some people to both liberal worldviews and depression, anxiety, etc. (even as they dispose others towards conservatism and mental well-being).

Alternatively (or perhaps additionally), there could be a direct causal relationship between liberalism and mental illness. For example, it may be that certain psychological conditions drive people toward liberal ideology. On the other hand, it could be that some aspect of liberalism routinely undermines adherents’ subjective well-being. A case could be made in either direction.

For instance, there is some evidence that children who are maladjusted (angry, aggressive, otherwise antisocial) are more likely to align themselves with left-wing parties as adults. Other studies have found that people who experienced abuse, insecurity, and trauma as children were much more likely to identify as liberal as adults. These populations are also especially likely to report mental illness as adults. Hence, it could be that much of the correlation between liberalism and mental illness is driven by people with mental distress favoring liberal ideology over conservatism.

Other studies have found that people who score highly on “Dark Triad” characteristics (narcissism, psychopathy, Machivallianism) may be especially likely to gravitate towards certain strains of “social justice” ideology (here, here, here, here, here, here). Likewise with many inclined towards authoritarianism (here, here, here, here, here).

A point of clarification is necessary here. The fact that many who are high in Dark Triad or authoritarian traits gravitate toward certain left-wing cultural movements (as a means of exercising power over others and advancing their own status and goals) neither entails nor implies that most people who subscribe to left-wing cultural views are, themselves, narcissistic, psychopathic, Machiavellian, or authoritarian. Nor is it the case that Dark Triad or authoritarian political associations skew uniquely left overall. As the links provided illustrate, there are right-aligned ideologies and social movements that are also attractive to Dark Triad and authoritarian personalities, even if they’re less well-institutionalized than “cultural Left” views within knowledge economy spaces (thereby providing them less opportunity to leverage ideology in the service of self-enhancement, or to exert influence within mainstream professional and cultural domains, as compared to left-wing dispositional peers).

In any case, although some combination of genetic/biological influences and an elective affinity between mental or emotional unwellness and left-wing political views may go a long way to explaining the general gaps in well-being between liberals and conservatives, they can do little to explain the huge and unilateral spike in depression among liberals in 2012, nor the divergent patterns between liberals and conservatives thereafter. Explaining these phenomena would require us to explore the extent to which ideology may influence mental illness (rather than vice-versa), and to account for how the influence of that ideology might’ve changed after 2011. It’s to these points we now turn.

Did the “Great Awokening” Significantly Exacerbate Psychological Distress in Liberals?

In addition to conservatism offering psychological benefits for adherents, it may be that some versions of liberal ideology impose mental costs on those who embrace them. That is, certain strains of left-wing views might render people more likely to be depressed, anxious, or unwell than they otherwise would have been.

A causal relationship of this nature could help explain the general gap between liberals and conservatives observed across time. However, it could also help explain the rapid rise in mental disorder after 2011. Insofar as certain strains of leftism may be pernicious to mental health, if those ideologies rapidly grew more prominent, or suddenly began to exert significantly more influence over U.S. institutions and culture, this would likely have a significant adverse effect on Americans’ mental well-being—including and especially among those who most eagerly embrace these views.

However, positing that the “Great Awokening” may have influenced levels of reported mental distress seems to beg a more fundamental question: are there compelling, empirically-based reasons to suspect that liberalism does not just correlate with adverse psychological states but might actually exacerbate depression, anxiety, or other problems among those who embrace it? The short answer is yes.

Cross-cultural studies have shown that more liberal countries, and more liberal regions within countries, tend to have higher rates of mental disorders. It’s been theorized that reduced levels of social constraints may be a key factor driving this pattern. In contexts where traditional forms of life, traditional social roles, and social structures are undermined, the acts of self-presentation, self-management, and self-creation become much more demanding and fraught. This, it has been argued, contributes to heightened anxiety and depression within liberal areas.

Research consistently finds that the Americans who give most frequently, give the highest shares of their income, or donate specifically to causes to alleviate human poverty and suffering are those who are right-leaning and religious. Despite these gaps in behaviors, liberals have a broader sphere of moral concern and tend to feel higher levels of empathy (even if those sentiments don’t lead them to incur actual costs and risks on others’ behalf in the same manner as conservatives). Liberals tend to be troubled not just by the state of their own nation and community, but by the plight of animals and nature, of people and events in other countries, by hypothetical and projected future trends as well as historical injustices—most of which the typical person has little-to-no meaningful control or influence over. This can be a source of significant depression or anxiety (or “moral distress” to borrow a term from health care).

Although liberals tend to be less emotionally stable than conservatives, they are also far more likely to prize emotionality and to dwell on their emotions and the emotions of others. They tend to react much more severely to unfortunate events—from public tragedies to political defeats to global catastrophes and beyond. Not only are their initial responses significantly more dramatic, but liberals are also adversely affected for longer periods of time.

Moreover, compared to conservatives, liberals are much more likely to find meaning in their lives through political causes or activism. They tend to follow politics much more closely and participate more in political action. However, following politics closely, and regular engagement on politics, has been shown to adversely affect people’s mental and physiological well-being (here, here, here, here).

Politics may also undermine liberals’ social relationships (which are, themselves, important for mental health). Surveys consistently find that liberals have more politically homogenous communities and social networks. They are also far more willing to avoid, break off or curb relationships over political differences. White liberal women are especially likely to strike this posture (here, here, here, here). They also happen to report especially high levels of anxiety, depression, and other disorders compared to other Americans. This may not be a coincidence: a willingness to “cancel” one’s family and friends over political or ideological differences is unlikely to enhance one’s happiness or well-being.

Here the discerning reader may object that perhaps the main reason for observed difference in reported mental illness across ideological lines is that conservatives are more likely to dismiss or stigmatize mental illness and may be less likely to seek help when they are struggling. In fact, as demographer Lyman Stone has illustrated, conservatives in the highest third of reported symptoms of mental disorder actually seem more likely to pursue assistance than liberals.

The main difference across ideological lines is that liberals are much more likely to seek out diagnoses even when they have moderate-to-low symptoms of poor mental health, whereas others do not.

The moral culture of many left-spaces may play an important role in driving these patterns. Sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning have argued that in many liberal, affluent, highly-educated spaces one increasingly gains moral status through association with formerly stigmatized identities—for instance by identifying as a racial, ethnic, or religious minority, a sexual minority, or as a person with a mental or physical disability. Unwellness can even be a monetizable asset contemporary left-spaces. As one social media influencer recently put it, “There absolutely is a concerted effort to really capitalize on mental illness and particularly on young women’s mental illness. It’s a very marketable commodity right now.”

Consequently, perverse incentive structures in certain liberal spaces may push many to seek out diagnoses even when they are not experiencing severe symptoms. Others who are not part of that moral culture would feel less pressure or eagerness to get themselves classified as “disabled.” This may help explain the partisan gap in reported mental illness.

Another consideration: highly-educated and relatively affluent white liberals are the Americans most likely to identify as “feminists,” “antiracists,” or “allies” or to hold far left views on “cultural” issues (here, here, here, here, here, here). However, according to many of the belief systems in question, affluent whites are the source of virtually all the world’s problems. That is, these ideologies villainize the very people who are most likely to embrace them.

Reflective of this mentality, white liberals view all other racial and ethnic subgroups more warmly than their own. There is no other combination of ideology and race or ethnicity that produces a similar pattern. This tension—being part of a group that one hates—creates strong dissociative pressures on many white liberals. This may help explain the racialized differences among liberals with respect to mental health.

Liberals, especially white liberals, are also much more anxious about interactions across difference. The perceptions, judgements, and behaviors of liberals change dramatically based on the demographic characteristics of the people they are engaging with or referring to, while conservatives are generally more consistent down the line (here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here). As a result of these tendencies, liberals (and white liberals in particular) may be more likely to second-guess their behaviors and motives, dwell on awkward past interactions, and worry about how others perceive them. This type of rumination, in turn, is associated with heightened anxiety and depression.

Analyses by political scientists Zach Goldberg and Eric Kaufmann have indeed found significant interactions between race and ideology with respect to reported mental struggles. White liberals are far more likely than anyone else to claim to have a mental illness or disorder. Whites who identify as “very liberal” or “liberal” are nearly twice as likely to claim mental illness as non-whites who share the same ideological identification.

However, the ideological gap in mental health is not purely something that manifests among whites. Non-white liberals are also significantly more likely to report mental illness than non-white moderates or conservatives of any stripe. In fact, there are reasons to suspect that certain strains of liberal ideology may exert uniquely pernicious effects among women and people of color.

In many Left circles, great efforts are made to sensitize everyone to historical and ongoing bias and discrimination. Women and minorities are told to attribute negative outcomes in their lives to racism or sexism. They are encouraged to interpret ambiguous encounters or situations uncharitably (i.e., as manifestations of racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.). These tendencies likely undermine the well-being of the very populations they are supposed to help.

Heightened perceptions of bias and discrimination are robustly associated with mental anguish, social strain, and adverse physical outcomes. The more people perceive themselves to be surrounded by others who harbor bias or hostility against them, and the more they view their life prospects as hostage to a system that is fundamentally rigged against them, the more likely they become to experience anxiety, depression, psychogenic and psychosomatic health problems, or to behave in antisocial ways.

On the one hand, this seems obvious. However, the implications are underappreciated: to the extent that certain strains of liberal ideology push adherents to perceive people and phenomena as racist, sexist, homophobic, etc.—when they otherwise would not have—this shift can predictably lead to increased levels of anxiety, depression, and other disorders.

This is not mere speculation: liberal ideology is associated with heightened perceptions of bias and discrimination. Liberal women, for instance, are significantly more likely than others to perceive themselves to have been victims of sexual harassment or sex-based discrimination. High levels of education exacerbate these tendencies (here, here, here, here).

Of course, it’s possible that these differences in perceived harassment and discrimination are based on objective realities—for instance, men in liberal spaces could be significantly more misogynistic in practice than men in other contexts. However, it seems more likely that the ideological perception gap in sexual harassment and discrimination is mostly a product of heightened sensitivity among liberal women, and highly educated liberal women, in particular, as compared to other Americans.

Likewise, among racial and ethnic minorities, perceptions of discrimination correlate strongly with educational attainment (which, itself, strongly informs ideological lean). Black Americans are significantly more likely to perceive themselves to be victims of prejudice and discrimination when they or their parents have higher levels of educational attainment. As a result of these heightened perceptions of discrimination, socioeconomic status has diminishing mental health returns for African Americans as compared to whites. Similar realities hold for Latinos and Asian Americans: higher educational attainment leads to heightened perceptions of discrimination—to the detriment of mental health.

For people of color, getting “educated” in America is to be cudgeled relentlessly with messages about how oppressed, exploited, and powerless we are, and how white people need to “get it together” to change this (but probably never will). Narratives like these grew especially pronounced during the post-2011 “Great Awokening.” The internalization of these messages may contribute to the observed ideological gaps in psychic distress among women and people of color.

And even when minorities don’t directly suffer from anxiety or depression, they regularly suffer because of these disorders nonetheless. Studies have found that the challenges of dealing with white liberal peers and their idiosyncratic neuroses and dispositions may be a key source of burnout for minorities in progressive spaces (here, here, here). More broadly, psychologist Jon Haidt and legal scholar Greg Lukianoff have argued (e.g., here, here) that many strains of liberal ideology fashionable among highly educated and relatively affluent Americans function, in practice, as a form of reverse cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Cognitive behavioral therapy encourages people to avoid global labeling and black-and-white or zero-sum thinking. It pushes people to abstain from hyperbole and catastrophizing or filtering out the good while highlighting the bad. CBT encourages people to resist emotional reasoning, jumping to conclusions, mind-reading, and uncharitable motive attribution. It tells adherents not to make strong assumptions about what others should do or feel, or how the world should be. Instead, patients are encouraged to meet the world as it is, and to engage the actual over the ideal. CBT instructs people to look for solutions to problems rather than focusing inordinately on who to blame (and punish). It tells patients to focus on controlling what they can in the present rather than ruminating on misfortunes of the past or worrying about futures that may or may not come to pass. It encourages people to see themselves as resilient and capable rather than weak, vulnerable, helpless or “damaged.” It is easy to see how popular strains of liberal thinking basically invert this guidance, likely to the detriment of adherents.

Insofar as certain sectors of the American public became more likely to internalize strains of liberal ideologies (U.S. whites became much more likely to self-identify as “liberal” after 2011), and to the extent that these ideologies gained increasing salience and influence in American society and culture after 2011 as a result of the “Great Awokening,” we might expect to see a significant, corresponding increase in depression, anxiety, and other disorders—particularly among the sectors of society most likely to embrace these ideological frameworks (highly-educated Americans, whites, liberals, women, young people). That is, in fact, what we do see.

Could the “Great Awokening” Have Exacerbated Distress among Conservatives Too?

The first figure above from Gimbrone et al. showed a dramatic rise in depression among liberal teens starting in 2012. However, there was also a rise among conservatives that started a couple years later and tapered off around 2017. The “Great Awokening” may have played an important role in the rise of depression among liberals, but could it have plausibly influenced conservatives as well? Again, the answer is yes.

Insofar as liberal peers became much more aggressive after 2011 in villainizing, suppressing, and punishing anyone who disagreed with them on contentious cultural issues, this likely had a pernicious effect on conservative teens too: being branded as a racist, sexist, homophobe, etc., and treated as a moral monster, can have major deleterious effects on one’s well-being.

However, attempts by external parties to shame people into compliance typically generate resistance, backlash, and deviance over the longer term. What we might expect to see, then, is a dramatic increase in negative affect among conservatives in the early years of the Awokening (as a result of being more aggressively mocked, derided, censored, and purged), followed by a leveling off or decline as right-aligned Americans increasingly dismiss and resist progressive attempts to characterize them as evil people.

On this model, liberals would move first, with the conservative increase in negative emotionality emerging as a reaction to shifts in liberal discourse and behaviors. However, there should be a disjuncture over time because the prevailing liberal ideologies would continue to exert a powerful influence over the mental state of liberals but would come to exercise diminishing influence over conservatives. These patterns are, in fact, reflected in the data.

There are, of course, many other factors at play in the observed trends after 2010—from evolving socioeconomic conditions for various subsets of the population (which, as I explain in my forthcoming book, play an important role in the timing of “Great Awokenings”) to technological changes and beyond. However, the different ways liberals and conservatives interpret the world and respond to adversity may also play an important role in the ideological polarization in subjective well-being independent of these other changes.

Conclusion

The well-being gap between liberals and conservatives is one of the most robust patterns in social science research. It is not a product of things that happened over the last decade or so; it goes back as far as the available data reach. The differences manifest across age, gender, race, religion, and other dimensions. They are not merely present in the United States, but in most other studied countries as well. Consequently, satisfying explanations of the gaps in reported well-being between liberals and conservatives would have to generalize beyond the present moment, beyond isolated cultural or geographic contexts, and beyond specific demographic groups. This essay has explored some of the most likely and well-explored drivers of the observed patterns:

- There are likely some genetic and biological factors that simultaneously predispose people towards both mental illness/ wellness and liberalism/ conservatism, respectively.

- Net of these predispositions, conservatism probably helps adherents make sense of, and respond constructively to, adverse states of affairs. These effects are independent of, but enhanced by, religiosity and patriotism (which tend to be ideological fellow-travelers with conservatism).

- Some strains of liberal ideology, on the other hand, likely exacerbate (and even incentivize) anxiety, depression, and other forms of unhealthy thinking. The increased power and prevalence of these ideological frameworks post-2011 may have contributed to the dramatic and asymmetrical rise in mental distress among liberals over the past decade.

- People who are unwell may be especially attracted to liberal politics over conservatism for a variety of reasons, and this may exacerbate observed ideological gaps net of other factors.

The amount of observed variance that each of these theories explain relative to one another is, at present, empirically unclear and hotly contested. However, the general pattern is clear: conservatives report significantly higher levels of happiness, meaning, and satisfaction in their lives as compared to liberals. Meanwhile, liberals are much more likely to exhibit anxiety, depression, and other forms of psychic distress.

Critically, these facts don’t tell us anything about which worldview is morally correct. Outside of Randian objectivism, it is widely acknowledged that what is maximally advantageous for oneself is not necessarily the most moral thing to do. Doing the right thing instead regularly imposes risks and costs on those who step up. Consequently, the fact that conservatism has practical advantages for adherents while liberalism may undermine well-being doesn’t necessarily tell us which ideology is more ethical to hold. Those are questions better suited for theology and philosophy than social science.

Likewise, the facts explored here tell us nothing about which worldview best helps us to most accurately capture reality. It’s not clear that there’s a tight correspondence between truth and well-being. In fact, as Nietzsche repeatedly emphasized, deep commitment to “the facts” may be an impediment to flourishing. Hence conservatism being more congenial to individual well-being may be perfectly compatible with claims that “reality has a well-known liberal bias.” Again, that’s a type of question that’s beyond the scope of this research.

Put another way: it’s a scientific fact that conservatives tend to be happier and more well-adjusted than liberals, and ideological gaps in well-being have expanded since 2011. The implications and applications of these realities remain wide open to interpretation.